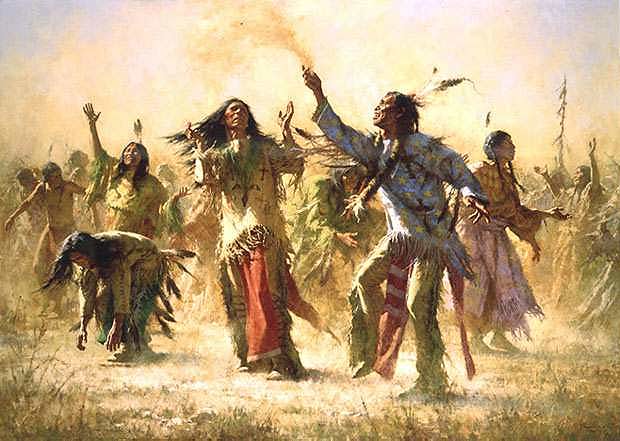

The ghost dance was a ritual the came to prominence in late 19th-century North America, as European colonists from the east began to push deeper into the continent. Native cultures throughout North America were already in a state of flux, as traditional ways of life were abandoned and the arrival of colonists was preceded by waves of disease and disruptive forces like alcohol and firearms. Much of the old native culture had already crumbled, but Christianization was only just beginning. The native cultures of the Americas were trying to find a new equilibrium that would allow them to maintain their historical traditions while interacting with new technology and invading colonists. Oddly, this is not so far from where First Nations cultures are today, struggling to find an identity and stuck in a broken and unfulfilled status quo.

Amidst this chaos, the ghost dance was created by a Paiute shaman named Jack Wilson after he claimed to have had a vision during a solar eclipse on January 1st, 1889. Wilson claimed that if the dance was performed at the proper intervals the evil in the world would be swept away, leaving a renewed Earth where food, love and faith were abundant and the First Nations would live in peace with the whites.

The ritual spread quickly through the tribes, and as often happens with religions and rituals based on peace, the message was quickly lost. Some tribes began to focus more on "sweeping away the world's evil" and began to see the ghost dance as a tool to help them do that. Warriors were taught that the ghost dance could be used to enchant garments and make them impervious to bullets. Of course, this was not the case, and eventually the resistance to the colonists was crushed. For a time, though, this simple dance galvanised resistance to the whites and actually made people believe they were invincible.

The ghost dance is only one example of this phenomenon: the self-fulfilling power of belief. Whether or not something is empirically true, mere belief in it can radically change the course of people's actions. The same phenomenon was occurring around the same time, during the Boxer Rebellion in China, where the rebels believed that magic power could be used to repel firearms. It is still evident today, where Islamic radicals are motivated to blow themselves up with the promise of forty virgins awaiting them afterward.

The phenomenon even showed up this last NFL season with Tim Tebow and the Denver Broncos. Many of Tebow's critics pointed out that the Broncos' turnaround was not due to his play, but instead to the improved play of the defence. What they fail to note, however, is that the reason the play of the defence improved was arguably their belief in Tebow. A couple of improbable wins and Tebow's blind faith with respect to both God and winning started to rub off on his teammates, and the belief itself, regardless of its truth, propelled the Broncos all the way from last place to the second round of the playoffs.

The self fulfilling power of belief is why I do new year's resolutions (and then don't write them down until March). I am sympathetic to the argument that new year's resolutions are almost always unachievable and are actually rather silly compared to an attitude that focuses on continuous, incremental improvement. However, I feel like making a point to craft the resolutions, writing them down, publishing them and measuring progress lends a certain gravitas or accountability to them and actually makes it more likely that I will achieve them, at least in part.

That said, here goes:

In 2011, I had five resolutions. I accomplished one outright by running a 5k in 19:51 in the rain on Mother's Day. I also ran my first 10k road race, and although the time (45 mins) wasn't great, I'm glad I did it. I also made progress on my bucket list by visiting three new countries in 2011: Belize, Honduras and Israel, but it was more modest progress than I would have liked. Two of my other resolutions resulted in very modest progress: eating healthier and simplifying my material possessions. My last 2011 resolution was to improve my arm strength, and although I made progress early in the year, I subsequently regressed and likely made no progress overall.

Therefore, I will carry over the four latter goals into 2012:

1. Make progress on and update my bucket list. I can potentially make progress towards visiting 100 countries, visiting Canadian national parks, running a marathon and/or running every day for a month. My time is also running short to see Peyton Manning play live so it will be important to see where he ends up. Updating the list will be the topic of a future post.

2. Eat healthier than the previous year. My sub-goals here will change slightly. I think I will try to keep linking intake of unhealthy snacks to number of workouts, as that was effective for parts of last year. I think I will initially try 150g of snacks per workout - roughly 2 workouts for every bag of chips. For unhealthy meals, as defined last year, I will change to limit unhealthy meals to only those times when I go with other people, as that was the biggest source of failure last year. The home-cooked meals idea is gone for this year.

3. Simplifying material possessions. Carried over as written last year. Obviously Dana will have to be on board with many aspects of this.

4. Improve arm strength. Carried over as written last year.

Additionally, I have a few new goals for this year:

5. Run a half-marathon. I have no time in mind here, as the distance will likely be a challenge in itself. I think that given how little I have run over the last 2-3 months, running the Calgary half on May 27th will be a stretch. Melissa's half in Banff on September 22nd is not a bad one for me to target because it is a tough course and not good for running a time, but would be scenic for a first race.

6. Run a 10k fast enough to score for the Nexen Corporate Challenge team. Last year this meant about 41 minutes. I would probably want to do a couple practice runs prior to the CC to establish a time but at the very least I want to improve my 10k time from last year and try and beat a few of Nexen's very strong ladies!

7. Save at least 50% of my after-tax net pay. For the first time in a couple years, I have no major capital expenditures planned for 2012. I paid for about two thirds of my car in 2010 and the rest in 2011, so I should be able to recognize substantial savings this year compared to those years. My budget forecast currently projects about a 51% savings rate, so if I keep to that I should be able to achieve this goal.

8. My last 2012 resolution is likely a multi-year one, but it stems from an article I read a few months ago that really struck a chord. I can recognize that although I am good at some of these things, there are others that concern me a little, particularly the first two on the list. I have already set in motion work on the second item by looking to transfer to a department that might be a little less onerous, but I may have to revisit that further over the long term.

The first item is where the real dilemma lies. I need to make strides towards a life that I am spending doing more of the things I like to do and am passionate about, and less of the other stuff to compensate. I want to read, write, debate, run, compete, make a difference, relax and spend time with friends, family and Dana. I have felt that since I graduated from university, I have been on a slow slide towards doing less of the things that I want to be doing and more of the other stuff. I need to evaluate why that is, prioritize differently and reverse that trend, starting in 2012.

Just as the ghost dance was meant to usher in a renewed Earth, each year is an opportunity to renew and improve oneself, and there are too few years in a life to waste any.